No Country Was Ever Ruined by Trade

Camp David

In April 1987, President Ronald Reagan delivered a radio address at Camp David warning Americans about the dangers of protectionist trade policies:

“You see, at first, when someone says, ‘Let’s impose tariffs on foreign imports,’ it looks like they’re doing the patriotic thing by protecting American products and jobs. And sometimes for a short while it works – but only for a short time. What eventually occurs is: First, homegrown industries start relying on government protection in the form of high tariffs. They stop competing and stop making the innovative management and technological changes they need to succeed in world markets. And then, while all this is going on, something even worse occurs. High tariffs inevitably lead to retaliation by foreign countries and the triggering of fierce trade wars. The result is more and more tariffs, higher and higher trade barriers, and less and less competition. So, soon, because of the prices made artificially high by tariffs that subsidize inefficiency and poor management, people stop buying. Then the worst happens: Markets shrink and collapse; businesses and industries shut down; and millions of people lose their jobs.”

Reagan added:

“Indeed, throughout the world there’s a growing realization that the way to prosperity for all nations is rejecting protectionist legislation and promoting fair and free competition. Now, there are sound historical reasons for this. For those of us who lived through the Great Depression, the memory of the suffering it caused is deep and searing. And today many economic analysts and historians argue that high tariff legislation passed back in that period called the Smoot-Hawley tariff greatly deepened the depression and prevented economic recover.”1

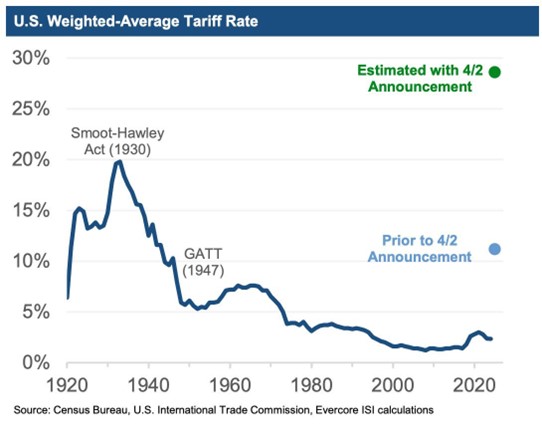

Almost four decades later, his warnings have been forgotten. On April 2nd, 2025 the U.S. government implemented a historic policy shift with implications for inflation, growth, global trade, and asset prices. In effect, it enacted the largest consumer-facing tax increase in over 50 years—without calling it one. Tariffs on imported goods have risen from 2.5% to somewhere between 24% and 34%, depending on how the new “reciprocal tariff” formula is applied. The last time the U.S. tariff regime was this aggressive, Calvin Coolidge was president, and the world was still on the gold standard.

The administration’s chosen formula has little basis in trade economics and even less in macro theory. It’s less about leveling the playing field and more about leveraging shock as a negotiating tool.

[1] Ronald Raegan Presidential Library, April 25, 1987.

Decoding the Numbers: 24% vs. 34%, and the French Lobster Colony That Broke the Model

Let’s put some structure around the chaos.

Some estimate the blended average U.S. tariff rate under the new regime at ~24%, assuming the reciprocal formula replaces existing product-specific tariffs across all imports.

Historical context: This would represent the highest average tariff rate since the Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930, which helped turn a recession into a depression.

Others, suggest the effective rate could be as high as 34%, particularly if focused heavily on countries with large bilateral trade surpluses (e.g., China, Vietnam, Mexico).

Historical context: A 34% average tariff would exceed even Smoot-Hawley’s peak nominal levels, making this the most aggressive protectionist policy in modern U.S. history.

[2] Evercore

But the real punchline is the method of calculation. Instead of basing tariff rates on concrete metrics like industry risk, non-tariff barriers, or VAT differentials, the administration used the following formula:

MAX(10%, (Imports – Exports) / Imports)

Not a country’s actual tariffs imposed on U.S. goods.

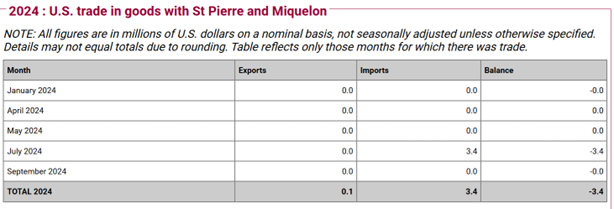

This means these tariffs are not simply a bargaining chip to reduce trade restrictions on the US, but rather a stickier policy meant to shrink the trade deficit. In other words, they may be much more prolonged than the market hopes. This has produced some of the most absurd policy outcomes in living memory. St. Pierre and Miquelon, a French overseas territory off the coast of Newfoundland with a population of just 5,800, now faces a 99% U.S. tariff rate—the highest in the world. Why? Likely because they export a nominal amount of goods to the U.S. (say, $3.4M worth of crustaceans) and import nothing in return.

[3] U.S. Census Bureau

Plug that into the White House algorithm—zero imports—and you get:

(0 – 100,000) / 0 = undefined, default to MAX function = 99%

Congratulations: we’ve now constructed a tariff regime that treats a French fishing village like its dumping steel on the U.S. economy.

This isn’t policy. This is an Excel formula gone rogue. And it perfectly encapsulates the administration’s approach: shocking, performative, and mathematically incoherent.

Tariffs Are Not Strategy. They’re Policy Theater.

There is no evidence this will reverse structural trade dynamics. U.S. manufacturing employment has dropped from 40% in 1950 to 7% today, and productivity, not trade, is the main driver. One estimate found 88% of U.S. manufacturing job losses from 2000–2010 were due to automation and robotics4. The idea that tariffs will drive a durable reindustrialization is a fantasy unsupported by either data or precedent.

Even Germany, a country that consistently runs trade surpluses, has experienced an equivalent decline in manufacturing employment share over the past two decades. As such, the notion that rebalancing trade will result in large employment gains misunderstands the nature of labor markets in post-industrial economies.

And no, tariffs cannot replace the income tax. Imports total about $3 trillion. The federal income tax generates $2.5 trillion5. Replacing that would require an 85% tax on imports, which would collapse trade flows and devastate domestic consumption. Even if you could do it, it would amount to a regressive tax that punishes lower-income households, those least able to absorb rising costs for food, clothing, and household goods.

[4] Bureau of Labor Statistics, “The Myth and Reality of Manufacturing in America” (2017)

[5] Congressional Research Bureau of Economic Analysis, Congressional Budget Office.

Inflation: Not All Supply Shocks Are Created Equal

These tariffs are inflationary in the short term. Evercore estimates they could boost core PCE by 1%–1.5% during mid-2025. That pushes the Fed into difficult territory:

- Headline inflation rises, even as labor markets cool and forward-looking data turns soft.

- The Fed may turn dovish not despite tariffs, but because they depress demand and corporate investment.

This creates an uncomfortable scenario where rate cuts coexist with sticky inflation. Markets can tolerate many things, but stagflation-lite is not one of them.

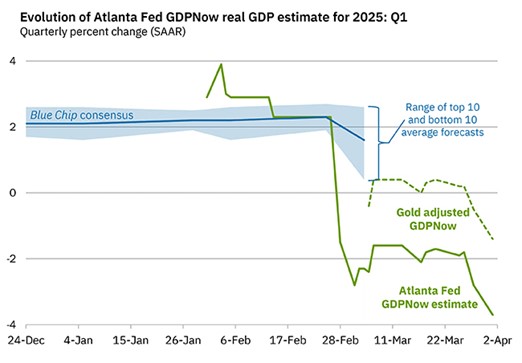

The Stagflation Risk: Tariffs as the New Supply Shock

Rising prices against negative growth is a real risk, one that cavalier trade policy may be underestimating. Restructuring the global trade order poses simultaneous threats to economic growth and price stability that the Fed may struggle to combat effectively.

[6] Chart provided by Atlanta Federal Reserve, as of 4/1/2025.

“Stagflation is like being forced to treat two opposing diseases with the same medicine.” -Paul Samuelson

The 1970s stagflation wasn’t a single event but a series of policy mistakes colliding with external shocks. The OPEC oil embargoes created economy-wide productivity shocks as the cost of this essential input quadrupled. When the Fed tightened in response, it crushed growth without addressing the supply constraints, requiring Volcker’s painful 20% interest rates to finally break the cycle.

Today’s scenario is different but creates similar economic conditions through tariffs. The inflationary pressure isn’t from overly aggressive monetary policy but from import taxation with immediate effects on consumer prices. Lowering interest rates won’t change this policy – and might actually increase inflationary pressure in rate-sensitive areas like housing.

So, how will Powell react?

The Fed has allowed inflation to run above target for over four years, and progress has stalled. While soft data shows growing labor market concerns, we’ve yet to see an employment breakdown that would dominate the dual mandate. There’s an argument that the Fed should look past policy-driven inflation and ease to counteract domestic slowdown. Treasury yields have already traded off materially, but given recent experiences, this may be a difficult narrative to sell.

Foreign Policy and Financial Confidence: The Risk of Retaliation

It’s not just about economics. Trade partners are preparing retaliation, and global capital allocators are watching with unease. Deutsche Bank flagged the potential for a “dollar confidence crisis,” citing the growing risk of:

- A structurally weaker U.S. dollar,

- Higher Treasury term premiums, and

- A reevaluation of U.S. institutional reliability.

Meanwhile, a growing narrative on the fringes, sometimes called the “Mar-a-Lago Accord”, imagines tariffs as just one leg in a broader strategic reset: weak dollar policy, sovereign wealth funds, zero-coupon Treasury restructurings, and defense cost-sharing with allies. But thus far, what we’ve seen looks less like a grand design and more like an improvisational campaign with no exit strategy.

Portfolio Positioning: What’s Priced In, What’s Not

- Equities: Margins are under pressure. The narrative of supply chain resilience may be stress-tested in real time. Companies with Asian manufacturing exposure—especially to Vietnam (46% tariff)—are already seeing valuation compression.

- Rates: With the Fed boxed in, expect a tug-of-war between growth-sensitive rate cuts and inflation-anchored hawkishness. The curve may steepen if term premium rises.

- Credit: Credit spreads may widen modestly, especially in consumer-sensitive and globally exposed sectors. Capex hesitancy and policy uncertainty are not great for leverage dynamics.

- Currency: The dollar has held up well, but the erosion of institutional credibility and risk of retaliatory de-dollarization campaigns could weigh on longer-term flows.

Final Thought: This Isn’t a Trade War. It’s a Policy Experiment.

Tariffs are being used not as a rational tool of economic adjustment, but as a blunt weapon in a populist theater of retribution. The outcomes—so far—include a tax on American consumers, rising inflation, declining business confidence, and global confusion.

This was supposed to strengthen the U.S. economy. Instead, it’s importing inflation, exporting confidence, and eroding the market’s ability to price risk. The scary part isn’t that this happened. The scary part is that it was deliberate.

IMPORTANT LEGAL DISCLOSURES

CURRENT MARKET DATA IS AS OF 04/02/2025. OPINIONS AND PREDICTIONS ARE AS OF 04/02/2025 AND ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE AT ANY TIME BASED ON MARKET AND OTHER CONDITIONS. NO PREDICTIONS OR FORECASTS CAN BE GUARANTEED. INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN HAS BEEN OBTAINED FROM SOURCES BELIEVED TO BE RELIABLE BUT IS NOT GUARANTEED.

THIS PRESENTATION (THE “PRESENTATION”) HAS BEEN PREPARED SOLELY FOR INFORMATION PURPOSES AND IS NOT INTENDED TO BE AN OFFER OR SOLICITATION AND IS BEING FURNISHED SOLELY FOR USE BY CLIENTS AND PROSPECTIVE CLIENTS IN CONSIDERING GFG CAPITAL, LLC (“GFG CAPITAL” OR THE “COMPANY”) AS THEIR INVESTMENT ADVISER. DO NOT USE THE FOREGOING AS THE SOLE BASIS OF INVESTMENT DECISIONS. ALL SOURCES DEEMED RELIABLE HOWEVER GFG CAPITAL ASSUMES NO RESPONSIBILITY FOR ANY INACCURACIES. THE OPINIONS CONTAINED HEREIN ARE NOT RECOMMENDATIONS.

THIS MATERIAL DOES NOT CONSTITUTE A RECOMMENDATION TO BUY OR SELL ANY SPECIFIC SECURITY, PAST PERFORMANCE IS NOT INDICATIVE OF FUTURE RESULTS. INVESTING INVOLVES RISK, INCLUDING THE POSSIBLE LOSS OF A PRINCIPAL INVESTMENT.

INDEX PERFORMANCE IS PRESENTED FOR ILLUSTRATIVE PURPOSES ONLY. DIRECT INVESTMENT CANNOT BE MADE INTO AN INDEX. INVESTMENT IN EQUITIES INVOLVES MORE RISK THAN OTHER SECURITIES AND MAY HAVE THE POTENTIAL FOR HIGHER RETURNS AND GREATER LOSSES. BONDS HAVE INTEREST RATE RISK AND CREDIT RISK. AS INTEREST RATES RISE, EXISTING BOND PRICES FALL AND CAN CAUSE THE VALUE OF AN INVESTMENT TO DECLINE. CHANGES IN INTEREST RATES GENERALLY HAVE A GREATER EFFECT ON BONDS WITH LONGER MATURITIES THAN ON THOSE WITH SHORTER MATURITIES. CREDIT RISK REFERES TO THE POSSIBLITY THAT THE ISSUER OF THE BOND WILL NOT BE ABLE TO MAKE PRINCIPAL AND/OR INTEREST PAYMENTS.

THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN HAS BEEN PREPARED TO ASSIST INTERESTED PARTIES IN MAKING THEIR OWN EVALUATION OF GFG CAPITAL AND DOES NOT PURPORT TO CONTAIN ALL OF THE INFORMATION THAT A PROSPECTIVE CLIENT MAY DESIRE. IN ALL CASES, INTERESTED PARTIES SHOULD CONDUCT THEIR OWN INVESTIGATION AND ANALYSIS OF GFG CAPITAL AND THE DATA SET FORTH IN THIS PRESENTATION. FOR A FULL DESCRIPTION OF GFG CAPITAL’S ADVISORY SERVICES AND FEES, PLEASE REFER TO OUR FORM ADV PART 2 DISCLOSURE BROCHURE AVAILABLE BY REQUEST OR AT THE FOLLOWING WEBSITE: HTTP://WWW.ADVISERINFO.SEC.GOV/.

ALL COMMUNICATIONS, INQUIRIES AND REQUESTS FOR INFORMATION RELATING TO THIS PRESENTATION SHOULD BE ADDRESSED TO GFG CAPITAL AT 305-810-6500.