When it comes to equity valuations, it’s easy to get lost in the weeds of earnings growth, margin expansion, and productivity gains. But at the end of the day, what every investor is trying to answer is this: Who deserves a premium multiple, and why? This question becomes more pertinent when you consider the underlying quality of today’s market leaders and the valuation premiums they command. Spoiler alert: some premiums are earned, while others might be overdrawn.

Margin Expansion: The Mirage or the Mechanic?

Margin expansion is one of the great white whales of corporate finance. Investors salivate at the idea that companies can consistently deliver wider margins. It feels like free money: the same revenue, but more profit. However, every percentage point of margin expansion has to come from somewhere.

If a company expands margins in a tight labor market, the math is simple: labor is losing. Fewer hires, stagnant wages, or operational efficiencies that eliminate jobs altogether. Alternatively, margin expansion might come from shifting costs to customers or leaning on the government’s balance sheet. Fiscal deficits have quietly underwritten corporate America’s margin expansion in recent years, acting as the silent partner to profitability. But government largesse isn’t infinite, and consumers can only bear so much before they start pushing back.

At the macroeconomic level, margin expansion often requires a broader redistribution of resources. Labor’s share of GDP—essentially, the portion of economic output going to workers—must shrink for corporate profits to expand. This creates tension, as labor income is also consumer spending, the lifeblood of economic growth. Without additional support from government spending or household savings, sustained margin expansion becomes a zero-sum game, where one sector’s gain is another’s loss.

Productivity: The Perennial Hopeful

Many turn to productivity growth as the saving grace for margins. The logic is straightforward: if workers become more efficient, companies can get more output per dollar spent. It’s a beautiful theory that works—to an extent. Productivity gains don’t happen overnight, and even when they do, their effects are modest. Consider this: a 2% productivity increase over a decade might lift nominal GDP growth by the same amount. Over decades, this incremental improvement compounds, but it still falls short of generating the kind of earnings growth that equity markets, particularly those buoyed by AI optimism, have priced in.

To put this into perspective, the advent of computers revolutionized productivity, but even then, their impact on annual productivity growth was limited to around 1% to 1.5% over a 20-year period1. Imagine achieving double that improvement—2%—over just a decade. It would be a remarkable feat, yet the nominal GDP growth boost would still be insufficient to meet the elevated earnings expectations embedded in today’s equity valuations.

Moreover, productivity growth—while important—does not change the fundamental relationship between corporate sales and GDP. At an aggregate level, S&P 500 sales are bound by the nominal GDP growth rate.

[1] Chicago Booth Review, February 2018.

[2] Chart provided by Goldman Sachs.

Even with meaningful gains in efficiency, productivity simply supports the existing economic structure; it doesn’t create a structural shift that allows earnings growth to accelerate beyond the economy’s underlying growth capacity. For every percentage point gained through productivity, companies must still grapple with the constraints of labor’s share of GDP and the broader macroeconomic environment.

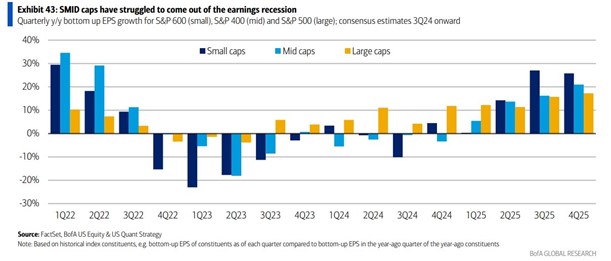

Productivity alone cannot deliver the kind of margin expansion and earnings growth that justify today’s elevated expectations for the have nots. What it does provide, however, is the backdrop against which companies must execute. And execution is where the separation between “higher multiples” and “everyone else” comes into focus. Notice how the expectations for mid and small cap companies are penciled in to outpace their large cap counterparts over the coming quarters:

[3] Chart provided by Bank of America.

Premium Multiples: Earned or Assumed?

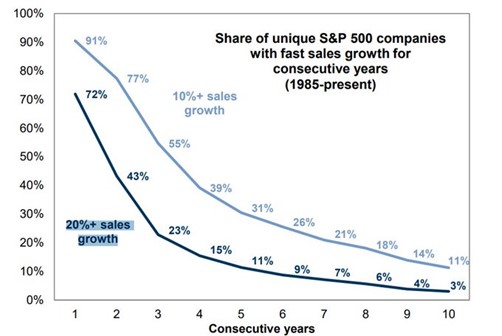

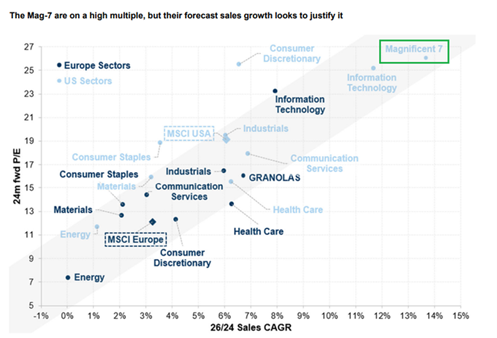

Let’s talk about multiples. Specifically, let’s talk about why some companies deserve to trade at 25x earnings while others languish at 10x. At a glance, it’s tempting to attribute the difference to growth rates. High-flying tech companies have set the bar for earnings growth expectations. The “Magnificent Seven” have redefined what it means to capture market share, and their ability to grow faster than GDP—at least for now—feels almost inevitable.

But it’s not just growth that warrants a premium. It’s the durability of that growth and the sustainability of margins. Netflix is a classic case study. The company didn’t just grow; it systematically took market share, forced competitors to adapt or die, and maintained pricing power along the way. That’s the kind of moat that justifies a higher multiple. But here’s the catch: the S&P 500’s premium multiple today assumes that every company can pull off a Netflix-like transformation. History suggests otherwise.

The Aggregate Assumption Problem

While individual companies can warrant a premium, the aggregate market multiple tells a different story. Median S&P 500 valuations remain elevated, driven by forward earnings expectations that look—how should we put this? —optimistic. As always, forward earnings are just that: expectations. And expectations have a habit of outpacing reality.

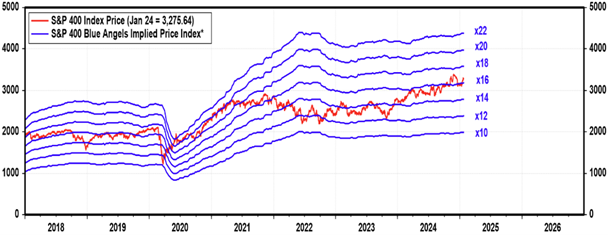

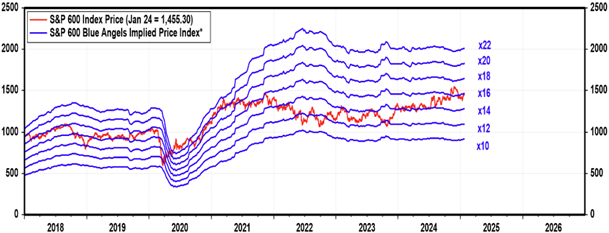

[4] Charts provided by Yardeni Research.

The issue isn’t just the lofty multiples of market leaders; it’s the valuation creep across the board. Investors appear to be pricing in a world where not only the “Magnificent Seven” but also their lesser peers achieve Netflix-like feats of margin expansion and earnings growth. That’s a lot of weight for an index to carry, particularly when the macroeconomic backdrop is less forgiving.

Disappointment: The Catalyst for Repricing

From an investor’s perspective, the zero-sum relationship within the fight for sales growth and margin expansion becomes most pronounced when selecting individual stocks for a portfolio. This dynamic underscores the case for owning the broader index, despite concerns about concentration in today’s indices. By holding a market cap-weighted index, the investor benefits from the ongoing battle for market share. As some companies thrive and others falter, the index naturally rebalances, capturing the net effect of this economic tug-of-war. This passive participation allows investors to reap the rewards of market leadership transitions without needing to pick winners and losers directly.

If there’s one constant in markets, it’s that disappointment drives cycles. High expectations breed vulnerability. When reality fails to meet those expectations, valuations adjust. We’ve seen this playbook before. In the absence of robust credit growth or meaningful macroeconomic tailwinds, the margin for error becomes razor thin.

The setup for disappointment is classic: a market rally fueled by growth surprises gives way to a leveling off as surprises diminish. Investors, intoxicated by past outperformance, extrapolate future returns without accounting for the underlying dynamics. Eventually, the gap between expectations and reality becomes too wide to ignore, and markets reprice accordingly.

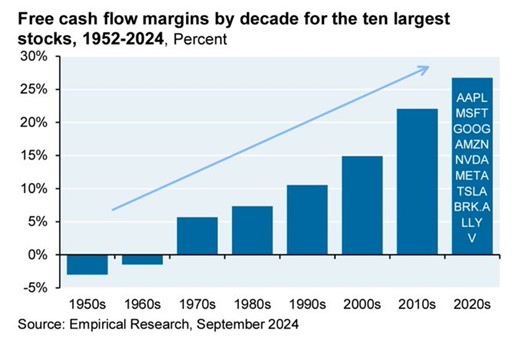

The Case for Higher Multiples—When Earned

None of this is to say that premium multiples aren’t justified in today’s market. They absolutely are—for the right companies. The S&P 500’s leaders are not the same companies that defined the index decades ago. The underlying quality of these firms, their market share dominance, and their ability to innovate warrant higher multiples than what traditional valuation models might suggest. But extending these premiums to the broader market is where things get precarious.

[5] Chart provided by Goldman Sachs.

[6] Chart provided by Empirical Research

As investors, the challenge is to separate the wheat from the chaff. Who can maintain margins without leaning on external crutches like fiscal deficits? Who can grow earnings sustainably without overreaching on forward guidance? And most importantly, who deserves to command a higher multiple in a world where disappointment can change the narrative in an instant?

The answers lie in the fundamentals. Growth is good, but durable growth is better. Margins matter, but only when they’re sustainable. And multiples? They’re earned, not assumed.

IMPORTANT LEGAL DISCLOSURES

CURRENT MARKET DATA IS AS OF 01/24/2025. OPINIONS AND PREDICTIONS ARE AS OF 01/24/2025 AND ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE AT ANY TIME BASED ON MARKET AND OTHER CONDITIONS. NO PREDICTIONS OR FORECASTS CAN BE GUARANTEED. INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN HAS BEEN OBTAINED FROM SOURCES BELIEVED TO BE RELIABLE BUT IS NOT GUARANTEED.

THIS PRESENTATION (THE “PRESENTATION”) HAS BEEN PREPARED SOLELY FOR INFORMATION PURPOSES AND IS NOT INTENDED TO BE AN OFFER OR SOLICITATION AND IS BEING FURNISHED SOLELY FOR USE BY CLIENTS AND PROSPECTIVE CLIENTS IN CONSIDERING GFG CAPITAL, LLC (“GFG CAPITAL” OR THE “COMPANY”) AS THEIR INVESTMENT ADVISER. DO NOT USE THE FOREGOING AS THE SOLE BASIS OF INVESTMENT DECISIONS. ALL SOURCES DEEMED RELIABLE HOWEVER GFG CAPITAL ASSUMES NO RESPONSIBILITY FOR ANY INACCURACIES. THE OPINIONS CONTAINED HEREIN ARE NOT RECOMMENDATIONS.

THIS MATERIAL DOES NOT CONSTITUTE A RECOMMENDATION TO BUY OR SELL ANY SPECIFIC SECURITY, PAST PERFORMANCE IS NOT INDICATIVE OF FUTURE RESULTS. INVESTING INVOLVES RISK, INCLUDING THE POSSIBLE LOSS OF A PRINCIPAL INVESTMENT.

INDEX PERFORMANCE IS PRESENTED FOR ILLUSTRATIVE PURPOSES ONLY. DIRECT INVESTMENT CANNOT BE MADE INTO AN INDEX. INVESTMENT IN EQUITIES INVOLVES MORE RISK THAN OTHER SECURITIES AND MAY HAVE THE POTENTIAL FOR HIGHER RETURNS AND GREATER LOSSES. BONDS HAVE INTEREST RATE RISK AND CREDIT RISK. AS INTEREST RATES RISE, EXISTING BOND PRICES FALL AND CAN CAUSE THE VALUE OF AN INVESTMENT TO DECLINE. CHANGES IN INTEREST RATES GENERALLY HAVE A GREATER EFFECT ON BONDS WITH LONGER MATURITIES THAN ON THOSE WITH SHORTER MATURITIES. CREDIT RISK REFERES TO THE POSSIBLITY THAT THE ISSUER OF THE BOND WILL NOT BE ABLE TO MAKE PRINCIPAL AND/OR INTEREST PAYMENTS.

THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN HAS BEEN PREPARED TO ASSIST INTERESTED PARTIES IN MAKING THEIR OWN EVALUATION OF GFG CAPITAL AND DOES NOT PURPORT TO CONTAIN ALL OF THE INFORMATION THAT A PROSPECTIVE CLIENT MAY DESIRE. IN ALL CASES, INTERESTED PARTIES SHOULD CONDUCT THEIR OWN INVESTIGATION AND ANALYSIS OF GFG CAPITAL AND THE DATA SET FORTH IN THIS PRESENTATION. FOR A FULL DESCRIPTION OF GFG CAPITAL’S ADVISORY SERVICES AND FEES, PLEASE REFER TO OUR FORM ADV PART 2 DISCLOSURE BROCHURE AVAILABLE BY REQUEST OR AT THE FOLLOWING WEBSITE: HTTP://WWW.ADVISERINFO.SEC.GOV/.

ALL COMMUNICATIONS, INQUIRIES AND REQUESTS FOR INFORMATION RELATING TO THIS PRESENTATION SHOULD BE ADDRESSED TO GFG CAPITAL AT 305-810-6500.