You’ve done all of the hard(er) work. The entire process of seeking out investment advice, learning what it takes to reach your goals, building the relationship with your advisor. They know what makes you tick, and you believe you can count on them. You’ve developed a strategy that is curated to you and your needs, now it’s time to put it to work. And then you hear, “I’ll let you know when it’s a good time to enter the market.” Wait, what? I thought we just talked about the long-term goals we’re headed for and built an allocation that we were comfortable with. What gives? Human error has a funny way of working its way into an investor’s process. Investors seek out every excuse in the book to not be in the market, despite the fact they just determined it’s in their best interest to be in it. We don’t dwell on why this phenomenon exists too much, because frankly we don’t expect this characteristic to disappear anytime soon. When it comes down to it, there really are just three ways to implement a portfolio. Whether it’s fear or greed or both, investors seem to gravitate toward market timing. Here’s why that’s a mistake.

Conceptually there are three approaches to implementing a portfolio:

- Lump-sum investment (full implementation of capital at once)

- Market timing (now’s not the right time, let me wait)

- Dollar-cost averaging (disciplined process)

The risks and potential, or perceived, benefits of each can become relatively straightforward.

But let’s unpack them a bit, starting with market timing. It is a natural reaction for investors to become hyper-aware of market conditions just as they are needing to put capital to work. This is a feeling that is inescapable for anyone and is what leads investors to think “now’s not the right time, maybe I should wait.” You can pick any reason to fill in the blank that leads investors to do this: valuations, market cycle age, recent run-up in price, recent downturn in price, geopolitical scenarios, etc. The risk here is conditions can persist, for better or for worse, much longer than most investors can tolerate. Therefore, you run the risk of not being invested because your personal requirements for the market haven’t been met.

Take valuations for example. You could have been concerned in 2013 as the S&P 500 was approaching the all-time highs last seen prior to the financial crisis in 2007. If trying to speculate on market direction kept you in cash, the opportunity cost has arguably been worse than experiencing some kind of market decline. For the last few years, any investor could have pointed to valuations once again being at or near all-time highs being too much of a risk for investing new capital. What’s the market done? Climb higher. And higher. Leaving many investors with cash in hand waiting for some type of correction in valuation, which can either happen over a series of violent moves lower, or over persistent periods of a trendless market (sideways price action).

One question we’d ask investors in this scenario is what good is it to miss a run-up in equities of 36% (2016 and 2017 calendar compounded return) just to invest after the 10% pullback you’ve been waiting for? In doing so you’ve sacrificed 20% of return by waiting for a correction (the net return following the correction in early ’18 from 12/31/15-02/08/18)1.

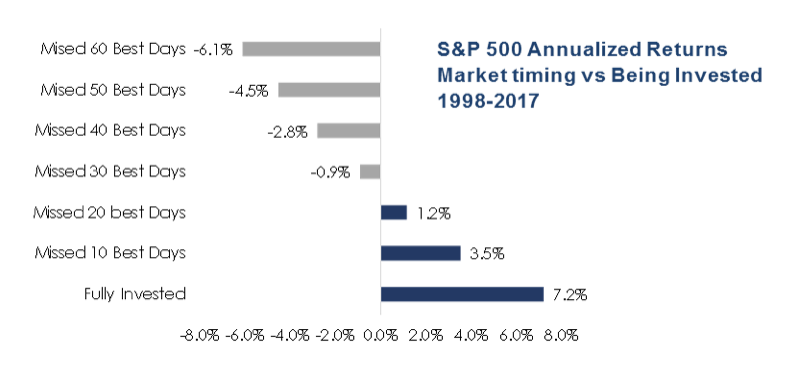

Research has shown that over extended periods, the market’s cumulative returns are often a product of a handful of exceptionally good days. Take a look below. Missing just the 10 best days due to jumping in and out of the market cuts your annual return by more than 50%2.

What’s often overlooked and underestimated when participants try to time the market like double-dutch is the likelihood of an investor being too shaken to put capital to work on the way down. The market is in the midst of a correction, investors are looking for the door. How confident are you that you’re the one who will be looking for the entrance? We know that from the peripheral, it seems like Warren Buffett has boiled this whole process down into a few quotes. But being fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful isn’t exactly as easy as it sounds. Nor do we think that constitute sound advice.

Regardless of the reason at any given time for an investor trying to justify waiting to implement assets, it boils down to the thought process of “this too shall pass, I’ll wait for normalcy within the markets.” But the problem is, normalcy within markets isn’t what many perceive it to be. Sanguine market conditions rarely exist, and when they do, they cause investors to be on edge (see 2017). What we as investors want to avoid doing is market timing with our implementation process. This can lead to missing exceptionally extended periods of market conditions that may not sit just right with investors but carry very long-term detrimental risks of not being exposed to the markets overall.

WE ALL FLOAT DOWN HERE

Lump sum investing has proven to be a successful investment approach in practice, but what it does carry is a natural risk most investors have not expressed comfort with (i.e. see above). We are routinely navigating a market that is unpredictable and tends to be irrational much longer than most investors are willing to tolerate. The risk of putting capital to work all at once, obviously, carries the very distinct possibility of investing at a market peak. A concern that has dominated the minds of investors for about five years now. But, what has proven to play out over the long term is putting as much capital to work as quickly as possible, especially for those with extended time horizons. There have been a number of studies done that back up investing lump sum totals at or near peak market valuations. And, the practice does in fact yield the greatest returns, albeit with the greater volatility. But fact is, being lured in by Mr. Market like Pennywise the Clown does sound pretty terrible. Let’s move to the next.

SET SOME GROUND RULES, ADHERE TO THEM, AND YOU’VE GOT A PROCESS

This leads us to dollar-cost averaging. The widest used implementation strategy given the fact that many investors tend to be investing on a monthly basis with their monthly income. Dollar-cost averaging (DCA) accomplishes multiple things for investors. For starters, it reduces the risk of implementing 100 percent of one’s assets at a market peak. Investors’ top concern. We can use this year as an immediate example. An investor who put 100 percent of their assets to work on January 1 might have looked at their portfolio at the end of the month and been very happy with themselves. Or perhaps they were timid and were trying to time the market and jumped on board toward the end of the month thinking the rally will persist because they’ve been convinced market anomalies such as the January Effect are a real thing. In each case these investors would have been met with a rude awakening in February and into March when they saw markets turn negative.

The alternative? Spread the implementation process across a predetermined timeline, regardless of conditions. We believe this spreads our market condition risk across an ample time period and allows for potential lowering the cost basis for our portfolio positions (i.e. potentially purchasing at a lower price in the second and thirdmonths). The flipside, of course, is what if you’re buying at higher prices? Well, then you’re buying into a positive trending market, a signal of strength, and we’re comfortable with that. And in the event of consecutive months of higher returns followed by a period of pullback, we’re still situated to potentially end up positive given the lower initial purchase prices and earlier start to capital being put to work (see note on market timing above).

Ultimately, this comes down to regret minimization. Discussing these concepts with investors can allow for us, as well as them, to learn what drives their regret the most. Missing out on short term upside? Or being exposed to potential significant losses at the start of their investment experience. We think any small premium paid for DCA over the long run benefits investor psyche and allows for a less contentious process of implementing a portfolio. If after discussing the risks associated with these implementation strategies still leaves you uneasy, then the risk profile may need to be revisited along with the total asset allocation.

SOURCE: This presentation is solely for informational purposes and should not be taken as investment advice. For further information, please contact one of our investment adviser representatives. Graph provided by GFG Capital. 1 Bloomberg. 2 J.P. Morgan.